The old Guyitt house on the Talbot Trail was crumbling for a long time. This 1840s farmhouse on the north side of the road east of Palmyra attracted a lot of attention in its abandoned state. Folks often stopped to take a picture of it.

Personally, I never did. I always meant to. Too late now. It's gone.

So I have to look online for pictures. Not a problem. So many people stopped to take a photo that it became one of the most photographed homes in Ontario, perhaps in Canada. And the photos were posted online:

|

| Screenshot, June 23, 2023 |

The Guyitt house during daylight. The Guyitt house at dusk. The Guyitt house in sunshine. The Guyitt house on a cloudy day. The Guyitt house covered in summer foliage. The Guyitt house surrounded by snow. The Guyitt house photoshopped. You get the idea.

Why was such a popular place demolished?

Last year the municipality of Chatham-Kent received one single complaint from a citizen concerned about the building's condition. Based on that, a building inspector was sent to look. The owner did have a "No Trespassing" sign up and a wire across the laneway. But the inspector deemed the building unsafe. (Duh. It was a shell.) There was concern that the signage wouldn't stop intruders from going in. So this week Chatham-Kent ordered the owner to have it demolished.

The incident raises a number of questions in my mind. First, whatever happened to personal responsibility? If a prowler insists on exploring an obviously dangerous wreck, and is injured, isn't that his own fault? What part of "No Trespassing" do some people not understand? Why is it up to the municipality to save people from themselves?

Second, why did a busybody complain about a ruin so many people admired? A recent article states an online petition dedicated to saving the building gathered over 4,000 signatures. Did the mischief maker not see all the people stopping to take photos? Did he or she have a personal grudge against the owner? While obviously beyond repair, the house was in the middle of nowhere and didn't endanger anyone else's property, as it might in the city. What real harm did it do?

Third, why did people love this ruin? Well, that's easier. 1) It looked haunted and mysterious. 2) Nowadays Ontarians have fewer pioneer homes to photograph. Many have been unsympathetically altered or torn down. 3) People love photographing ruins. In fact, there's a movement in photography called "ruin porn," chronicling the decay of the built environment.

Fourth, why do people like ruins at all? Anywhere? Wouldn't you think they'd make people uneasy? After all, we, like our buildings, will one day be gone. No matter how much progress we make as a society, we'll end like the Guyitt house. Or Pompeii. Or much of Detroit. Few of us like to be reminded of our own mortality.

These may be the reasons:

* Curiosity. Visitors wonder: Who lived there? Why did they leave? What would they think if they saw their home now? The past is more interesting than the present.

* Nostalgia. Ruins remind people of the "good old days." Old buildings, even in bad shape, remind us of simpler times.

* Local architectural history. Ruins provide a record of historic building methods, local materials, how earlier inhabitants adapted to their environment. Modern buildings tend to be the same everywhere, all over the world.

* Tourism. A ruin can be a draw to a certain area. When city dwellers go on Sunday afternoon drives, we like to see things we don't see at home in the boring suburbs. That includes ruins.

* Aesthetics. Let's face it, there's a strange attractiveness in seeing something made by humans gradually destroyed by the ravages of time and nature. Ruins are romantic. They spark the imagination of artists, photographers, and writers.

And my last question. I believe the Guyitt house might have attracted a few tourists to the Talbot Trail. There was certainly no other reason to visit Palmyra. (If you blinked, you'd miss it.) So when a place is as obviously admired as the Guyitt house, shouldn't the municipality have a better process in place than destruction after one complaint?

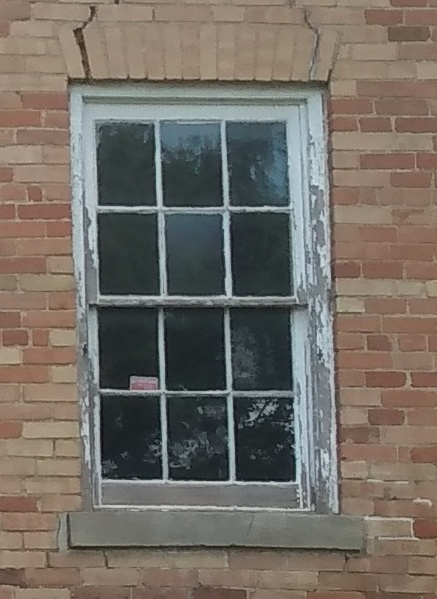

|

| Abandoned home near London, photographed 2022. How long will this stand? |