|

| No. 4 Fire Hall, 807 Colborne St. Built 1909 in abstract Italianate style with simplified Tuscan Tower. Still in use and apparently haunted. |

|

| Former Fire Station No. 3, 160 Bruce St. Built 1890-91. Used until 1975. Now apartments. |

History, Architecture & Genealogy in the Forest City and Beyond

|

| No. 4 Fire Hall, 807 Colborne St. Built 1909 in abstract Italianate style with simplified Tuscan Tower. Still in use and apparently haunted. |

|

| Former Fire Station No. 3, 160 Bruce St. Built 1890-91. Used until 1975. Now apartments. |

Sheri is donating $20 from the sale of each of her 10"x10" archival prints to the Black Walnut Fire Fund. The prints, $70 each, are scanned and printed locally at Colour by Schubert. Anyone interested can find Sheri Cowan Art on Facebook and Instagram or email her directly at sherimcowan99@gmail.com.

Update, August 2023: Black Walnut has revealed their plan to rebuild. Their new building will look "strikingly similar" to what was lost due to arson in April.

For some reason, a company called Mount Elgin Development is building cookie-cutter homes around the site. And needs to demolish the old home to do so. Once he's demolished Elgin Hall, the developer has offered to build a new apartment structure on the site with a façade that would mimic the “style” of the old house using the existing building materials. Oh goody! Another replica like the Sir Adam Beck Manor in London (see No. 4 here). The developer also states the building is in poor shape. Of course it is. Guess who let it get that way?

Last year a group of concerned individuals trying to save the building felt they’d made some progress towards designating the structure and selling it. But the developer refused an offer of more than a million dollars from Garth Turner, who has won awards for heritage restoration projects from Heritage Canada, among other organizations. Turner is a great-grandson of Bodwell.

Southwest Oxford Council met yesterday, April 18, to discuss placing a heritage designation on Elgin Hall. Unfortunately, they voted 4-3 to not grant heritage designation. Despite the fact that the building meets four of the criteria required for heritage designation (only two are needed) the developer can now apply for a demolition permit and is expected to do so.

My pictures were taken last year. I assume the deterioration is even more advanced at this point.

|

| Attractive recessed front doorway. |

|

| Advanced deterioration to rear wing. At least the front might have been preserved. |

|

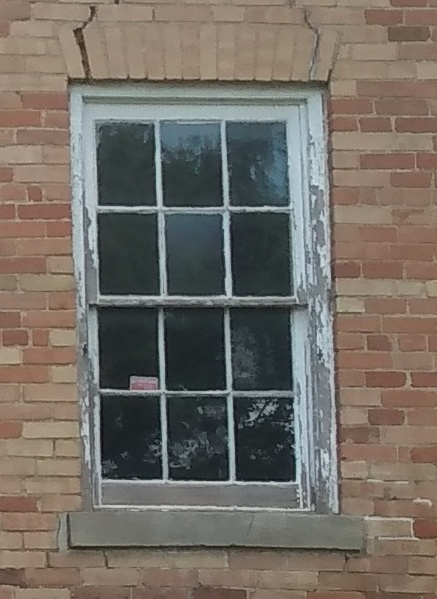

| Note 6 over 6 wooden sash. |

Update, May 2, 2023: The developer smashed the house to bits yesterday. To add insult to injury, the demolition company chose to make jokes about the building on their website.

Our architecture just doesn't get any respect. At the very least this home could have been deconstructed, not demolished, so that its windows, bricks, and interior fixtures could be used in another old building being restored.

Much needed repairs to sewers and water lines have led to a need to cut down trees, mainly around Regent Street and Fraser Avenue. Originally the city meant to remove 41 trees. Then the number was reduced to 38. The trees in question have been marked with white rings.

Old North neighbours have fought City Hall, protesting the tree removal, and signs have appeared on the marked trees. These folks aren't just treehuggers. While I don't live at Regent and Fraser, I do live in Old North and I understand that part of the charm of our neighbourhood is the mature trees. The removal of a large number could drastically change the atmosphere of the whole area.

Of course, the City of London isn't just being mean to trees, regardless of what some Old North kiddies might think. This interview with a city staffer explains the need for infrastructure renewal and the risks involved in not removing the trees. Note: She states that London removed 579 trees in 2022 but planted 8,874, over half of which were on city streets, not parks. The situation is obviously complex. The city does plant saplings as well as pruning and chopping mature trees.

All this makes me think about the continued use of the nickname "Forest City." Not only is it used in the above linked article, but by many London businesses, and - ahem - in the name of my own blog, because I can't resist using it either. Heck, even the city logo features a tree. Could there be some irony here? Should the Forest City really be cutting down trees?

The earliest known use of the term was on January 24, 1856, when the London Free Press and Daily Western Advertiser referred to London as "This City of the Forest." The first organization to use the name was Forest City Lodge, No. 38, IOOF, founded in 1857.* Since then, the name has appeared everywhere - on base ball clubs, colleges, churches, festivals, a Thames River steamboat, even a cannabis shop. But why? Is it really because of our lovely forest canopy?

Most people assume the term is meant as a compliment - see here and here. Although here it says the British government coined the term to make fun of John Graves Simcoe. Personally, I think historian Orlo Miller was correct when he stated there is a "widespread misunderstanding of the origin of the city's nickname, the Forest City. It was so called not because of the tree-lined streets, but because for many years it inhabited a cleared space in the encompassing forest."** Simcoe may have wanted his "New London on the Thames" to be the provincial capital but settlers in surrounding areas were amused by the fact that there was nothing here but trees. Our nickname was a pioneer joke.

That being the case, maybe Londoners should get over their Forest City obsession. Maybe too many residents can't see the forest for the trees?

I'd like to see a compromise between updating infrastructure and saving Old North's ambiance. After all, we do need toilets as well as trees. An April 13 City Hall Open House suggested such an arrangement might be possible. A pilot project could potentially spare an additional 16 trees, leaving only 22 to be chopped. Let's hope London and its tree-loving residents can find some middle ground - with trees on it, of course.

A worse change in the look of "Old" North is when earlier homes are demolished to make way for inappropriate infill. As an example, a house similar in size to the building at left was recently razed and replaced with the one on the right. There's more than one way to destroy a neighbourhood's atmosphere.

* Dan Brock, Fragments From The Forks. London & Middlesex Historical Society, 2011 pp. 49, 52.

** Orlo Miller, London 200: An Illustrated History. London Chamber of Commerce, 1992, p. 118.

Old photographs provide an interesting gateway to the past, showing us the fashions, hairstyles, homes, workplaces and communities of yesteryear. My family never threw anything out, so I'm fortunate to have old albums and loose photos featuring my relatives and the places they lived. I'm even luckier to have most of them labeled so I know who and where they are with a rough idea of the date.

As an example, here's a photo of 117 McGregor Avenue, Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario, identified by a relative at bottom. (It might have been neater to write on the rear but the photo can always be cropped if necessary.) I was aware that my great-grandparents, Robert and Fanny Moore, lived at this address in the Soo, but wouldn't have known this was the house if their granddaughter hadn't added the address sometime in the 1980s or 90s. Of course, nowadays you can also search an address on Google Street View, which I've done, so I know the house is still standing.Like many people, Robert and Fanny's daughter Helen (my grandmother) arranged photos in an album. The page below shows how she dated the pictures and identified some of the places. Her daughter added another caption in later years to identify Helen's sister, Kathleen, in the bottom centre photo.

"Doc Shepherd," by the way, appears to be a young lady in a fake beard. No doubt there's a story there, now lost.The Presbyterian Church Heritage Centre (PCHC) is moving into Carlisle United Church, in the hamlet of Carlisle, near Ailsa Craig in Middlesex County.*

Formerly the National Presbyterian Museum, the PCHC was located in St. John's Presbyterian, Toronto, from 2002 to 2021. But that church is currently being renovated into condominiums, forcing the Heritage Centre to find a new home. The new location will be this quaint country church built in 1879.

Like many congregations, the Carlisle church started out in an earlier building. Carlisle Presbyterian Church was founded in 1858 in a more primitive structure, replaced as soon as funds became available. The congregation joined the United Church of Canada in 1925.

But recently, like many rural congregations in the 21st century, Carlisle United has been struggling. With 19 members left in the congregation, continued use of the building was becoming impossible. Having the PCHC move in has brought new life to these folks, even though they've had to worship in the church basement. The former upstairs sanctuary will be renovated into an exhibit hall.

|

| Temporary basement sanctuary |

The move of the PCHC hasn't been easy or cheap. A fundraising campaign was necessary to increase the load-bearing capacity of the Carlisle church's sanctuary floor from 40 lbs. per sq. ft. to 100 lbs. per sq. ft. This involved removing the ceiling in the downstairs hall so the contractors could add the necessary reinforcement joists. But the pandemic allowed the necessary work to proceed easily, since there was no weekly worship service.

|

| Pews are currently stored in the future site of a replica pioneer sanctuary. |

|

| Magnificent memorial windows in what will become the upstairs exhibit hall. |

|

| Victoria Inn. Note Middlesex Heritage Trail sign out front. |

* A big thank you to Curator Ian Mason for information and to local resident Doug Carmichael, member of the Advisory Committee for the PCHC, for the tour of the church interior.

Update, December 19: Latest word is that the PCHC has received a $100,000 grant from The Presbyterian Church in Canada to finish the project.

First, why is it called Port Burwell? Because Col. Mahlon Burwell (1783-1846) surveyed the land here, completing the job in 1810-11. While dividing Bayham and Malahide townships into lots for settlers, he selected a block of land in Bayham for himself at the site that is now the village. Eventually, about 1830, he surveyed his plot into streets and building lots as well. He likely recognized that the nearby Big Otter Creek and harbour would provide a useful water route for landlocked communities to the north. In time, Port Burwell became a shipbuilding and fishing harbour and an export point for lumber and farm produce from surrounding townships. It wasn't really until the 1920s, in a more leisurely age, that the port became a summertime tourist destination, known for its beach.

|

| Burwell family graves at Trinity Anglican. |

|

| HMCS Ojibwa |

|

| Port Burwell postcard, dated 1909 by a former owner (The blogger's collection). |